Volumetric Displays

There are many types of volumetric displays and various ways we could classify them. Below we'll cover volumetric displays that use the principles of using mechanical or persistence of vision illusions to create images, and another version that uses layered screens to create a sense of volume. In a separate section we'll cover light field displays that have another take on this whole approach.

Volumetric Displays (Mechanical/Swept Volume/Persistence of Vision)

With Volumetric Displays, there are a couple different flavors, and in this section we’ll cover displays that work with the principle of persistence of vision, and are also known as swept volume displays. Volumetric Displays have been discussed in science fiction for decades and have been researched extensively since the 1960’s. Here is a 1969 paper from Bell Labs on a technique that uses a loudspeaker to vibrate a reflective mylar sheet in sync with a CRT to make an image volume.

This type of volumetric display usually uses a 2D display element in addition to a mechanical apparatus to move the display quickly enough (either laterally or radially) to give the illusion of volume. You can buy persistence of vision (POV) LED toys at carnivals and festivals that are the same basic idea that is found in the more complex setups discussed below. Crayola even made a toy a few years ago called the Digital Light Designer that let kids draw on one of these displays in real time. There are also more sophisticated LED based setups such as the viSio or voLumen that are mentioned in the links section.

These volumetric displays allow for one of the best impressions of 3D physicality and presence because the viewer can walk around and view different angles of the same image. The downside is that their mechanical nature makes them difficult to scale to larger displays with finer resolution, and the fact that they are moving so quickly can make them quite dangerous in certain situations. Some techniques can also be difficult to capture reliably or smoothly on video because the refresh rate may be out of sync with the camera’s frame rate.

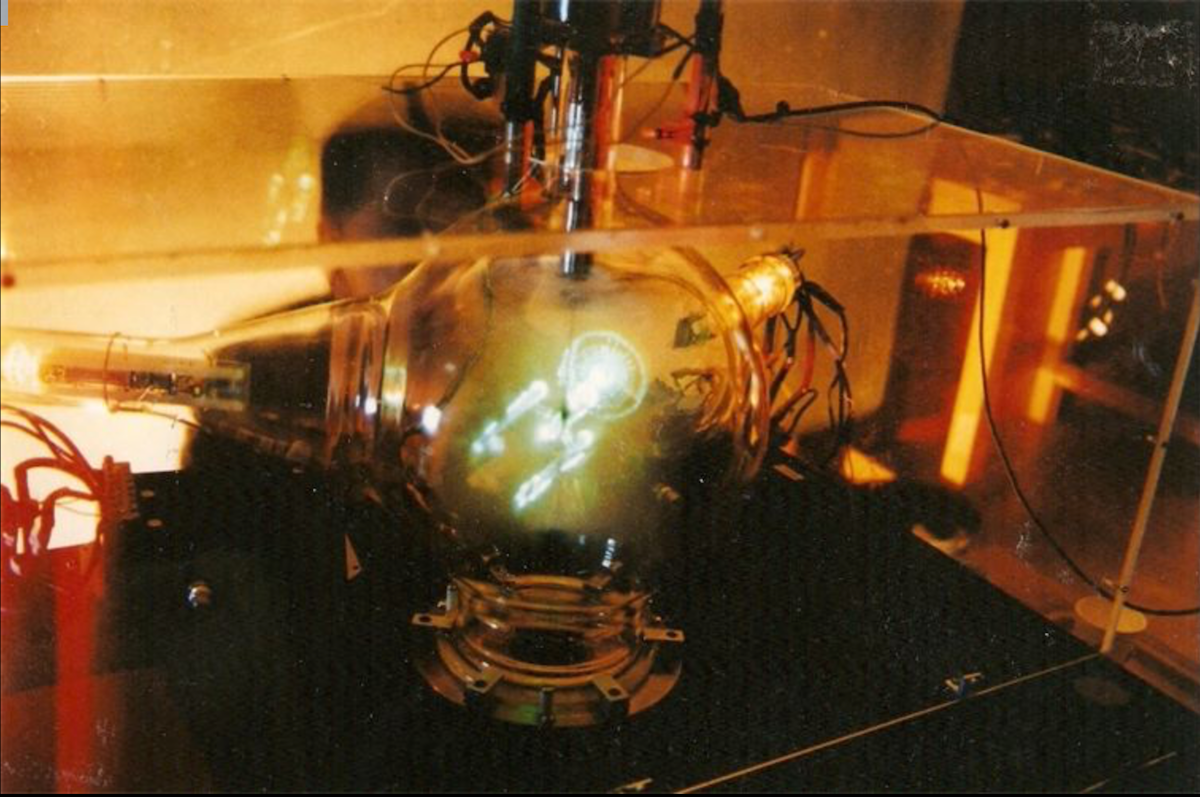

There have also been attempts at combining mechanical motion with more sophisticated displays like CRTs, projectors or LCDs. One of the earlier successful examples of these screens is Barry Blundell’s volumetric cathode ray tube work. He did some experiments in the 1990’s that used a specially designed glass tube, a spinning phosphor plate and multiple electron guns. Here is a video of that display in action.

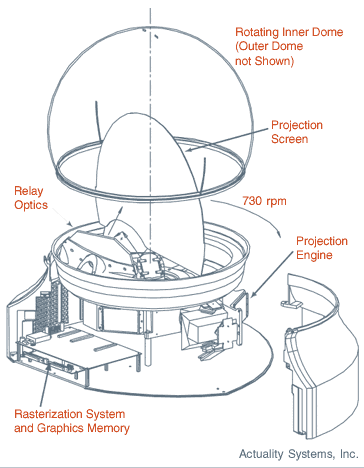

The Perspecta by Actuality Systems came in 2001 and followed a similar approach, but used specialized projectors and a rotating screen instead of electron guns. Here are some stats on the capabilities of the early version of the Perspecta:

“This computation is performed on a high-end NVIDIA GPU within the Volume Rendering Unit, and the results are stored in the Core Rendering Electronics (CRE). The CRE drives three Texas Instruments DMDs (Digital Micromirror Device) at approximately 6,000 frames per second with these slices, which are projected onto a diffuse screen that rotates at 900 rpm. The result is a crisp, bright, 3D image that can be viewed from any angle.”[Link]

Voxon Photonics

A more recent version of this type of display is the Voxon VX1 by the Australian company Voxon Photonics. Their former product was the Voxiebox. These displays use a high speed scientific projector and a rear projection platform that is moved up and down extremely quickly. The movement of the platform, the refresh rate of the projector and the content that is being drawn are all synced together by software. As the platform moves, a different slice of a 3D image is projected. As these slices are projected, the viewer’s brain assembles them into a persistent volumetric image. Each "pixel" on the display would be refered to as a voxel or volumetric pixel.

The Z axis resolution of the Voxon display is primarily limited by the frame rate of the projector and the lateral motion of the projection platform. There are also challenges with scaling this display to a considerably larger size for a number of reasons. Moving a much larger platform up and down a greater distance at a rapid pace isn’t outside of the realm of mechanical possibility, but it would be a different engineering challenge to make this display several meters wide and move up and down a few meters multiple times in a second. A larger platform also requires a brighter specialized projector, which comes at its own cost.

Perceptually, the Voxon style of display is suited to some particular visual aesthetics — it is better at showing certain types of graphics than others. The projected light is additive on each slice, so while one surface appears solid, it also combines with the light behind it — this is similar to the issues faced by volumetric projection in the other section. This makes very dense imagery move towards the white end of the spectrum as different slices add together for the viewer. Vector style imagery with points and lines tend to be more successful ways to represent solid shapes.

Other Volumetric approaches:

Another more artfully focused example of a mechanical volumetric display is Benjamin Muzzin’s piece Full Turn. Benjamin took 2 LCD panels, stuck them back to back and spun them at very high speeds. The power and video signals were passed in using a specially designed slip ring. The bottom ring is fixed and has one end of a cable attached to it. The top layer spins with the LCDs and maintains electrical contact via metal brushes that run in circular channels. As the LCD spins faster than the refresh rate of the screen, it allows it to render volumetric images that move and shift. In comparison to the Voxiebox, this particular implementation presents a different challenge when trying to form coherent 3D images because of the radial motion as opposed to lateral motion. The primary limitation on this sort of display would be the refresh rate of the LCD. LCD's tend to currently be in the 60-240hz range, and this project likely used a 60hz display, so its ability to flash and show more precise aspects of spun visuals would be a bit more challenging.

Other Swept Volume Displays

DIY Swept Volume Volumetric display from "Ancient James" in New Zealand that utilizes 3D printed parts and a Raspberry Pi to render a real time 3D scene

Volumetric Displays (Multiple Layered Screens)

There are a few different types of this type of volumetric display. One type is known as a Light Field Display or a Polarization Field Display and uses a series of layered LCD’s (or other transparent media) to create an illusion of depth via parallax. This is a simplified explanation because there are a lot of nuanced variations on this concept. The Nintendo 3DS is a well known version of this type of display — it uses 2 stacked LCD’s — the bottom one alternates dark bands so that each eye sees the version of the image that is intended for it.

By stacking each display on top of the other, you are able to create volumetric effects with 3 dimensional content, or more slipping parallax effects with 2D content. The depth resolution is limited by how many displays you can stack on top of each other. It also becomes more difficult to backlight all of the stacked displays so that everything is visible. Each display, its components and polarizing film will cost a little bit of luminance and clarity for the viewer. If the screens are far apart, there is also the possibility of internal reflection between two adjacent screens that can impact the contrast.

When using this type of display technique to show content, there are a few different approaches and challenges. The most straightforward method is to chop up your images into different depth layers so that you can achieve parallax by displaying each layer on a different screen. This is similar to the method of hand drawn cel animation where the background landscapes are on a different layer than the characters. To achieve more of a 3D volume effect with this method, you would have to incorporate viewer eye or head tracking into the display software in order to display multiple viewpoints in real time. The screens are also only viewable on 1 or 2 sides of a cube, instead of 4 or 5 sides. Your Z-dimension is constrained by how many displays you can stack on top of each other. Blending colors across multiple screens is also a challenge. Stacking dark colors will turn muddy at the end and stacking red green and blue won’t necessarily make white as with other additive light methods. Color filters also impact the brightness, and some projects use grayscale monitors instead.

Getting a video signal to each display is another technical challenge, depending on how many layers you are trying to drive. If you have 6 stacked displays at 1920x1080 — you need to be able to render six 1080p streams at once and keep them all synced together.

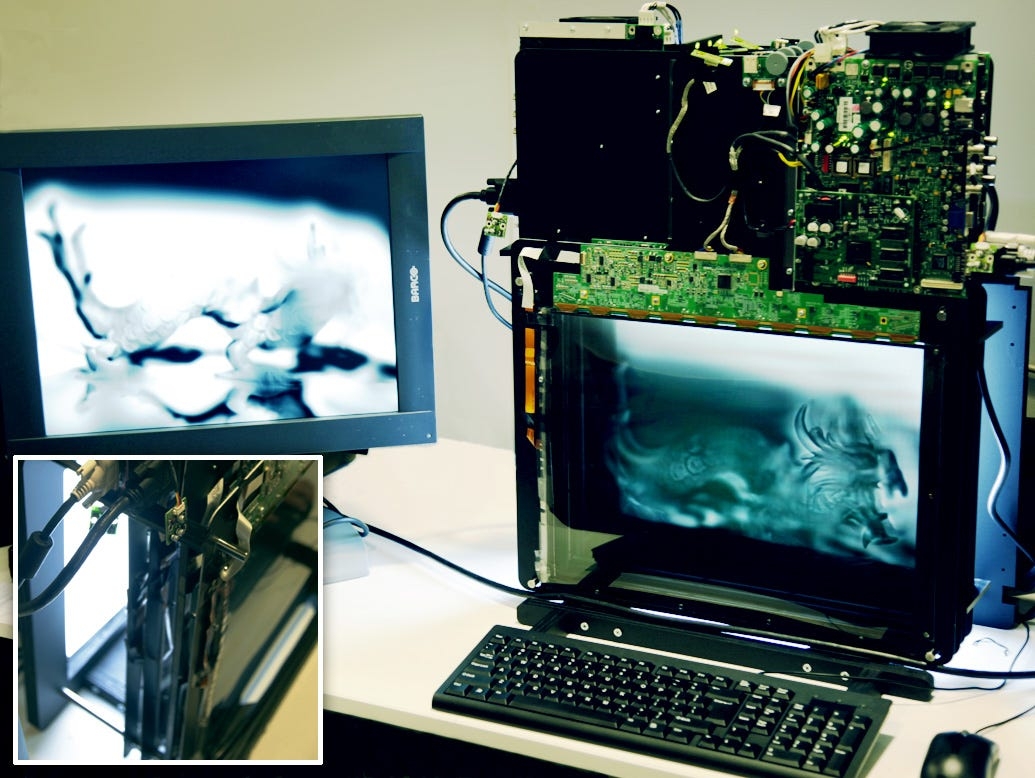

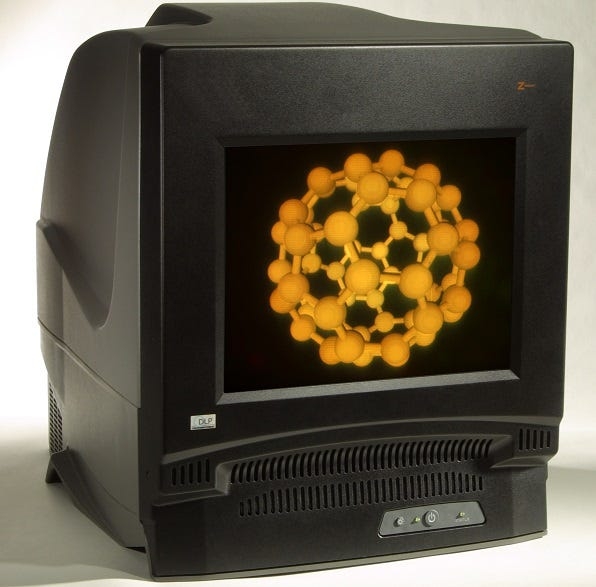

LightSpace Technologies has a display that was formerly known as the Depthcube that uses a high speed projector and a series of about 20 LCDs that are used as optical stops, so that each layer of depth can be halted at the correct location. By using special antialiasing techniques, the physical space between the layers can be smoothed so it doesn’t feel so stepped. Here is a writeup with more technical details on how it works. This display has been in development since the early 2000s and has been commercially available at an unknown price point. The primary use case of one of these displays has been in engineering or medical applications. Here is a video of it in action.

There are some versions of layered screens or display volumes that don’t stack multiple LCDs but combine them with things like layered Pepper’s Ghost, multiple projections on scrims, transparent acrylic, or LED cubes.

Around 2016, Looking Glass Factory developed Volume which was poised to be an affordable multiplane display. It achieved its effect by means of a projector and about 12 layers of angled material that catches a small sliver of the projector’s raster. They used a custom plugin for Unity that allows you to drop a 3D scene into their renderer and have it slice it up appropriately for their volumetric display. Eventually the Volume was discontinued for their newer models that utilize autostereoscopic lenticular displays.

Volumetric LED

There are also many pieces or products out there that use a 3D volume of individually addressable LEDs to create a layered volume with more viewing angles but a lower visual fidelity.

LEDPulse's Dragon displays are a productized version of this approach.

Other DIY Approaches

Last updated